Block ciphers

A block cipher consists of an encryption algorithm and a decryption algorithm:

The encryption algorithm (E) takes a key, \(K\), and a plaintext block, \(P\), and produces a ciphertext block, \(C\): \(C = E(K, P)\).

The decryption algorithm (D) is the inverse of the encryption algorithm and decrypts a message to the original plaintext, \(P\): \(P = D(K, C)\).

Since they are the inverse of each other, the encryption and decryption algorithms usually involve similar operations.

Security goals

In order for a block cipher to be secure, it should be a pseudorandom permutation (PRP), meaning that as long as the key is secret, an attacker shouldn’t be able to compute an output of the block cipher from any input.

IOW, as long as \(K\) is secret and random from an attacker’s perspective, they should have no clue about what \(E(K, P)\) looks like, for any given \(P\).

Codebook attack

Two values characterize a block cipher: the block size and the key size. While blocks shouldn’t be too large, they also shouldn’t be too small; otherwise, they may be susceptible to codebook attacks, which are attacks against block ciphers that are only efficient when smaller blocks are used.

The codebook attack works like this with 16-bit blocks:

Get the 65536 (\(2^{16}\)) ciphertexts corresponding to each 16-bit plaintext block.

Build a lookup table—the codebook—mapping each ciphertext block to its corresponding plaintext block.

To decrypt an unknown ciphertext block, look up its corresponding plaintext block in the table.

Slide attack and round keys

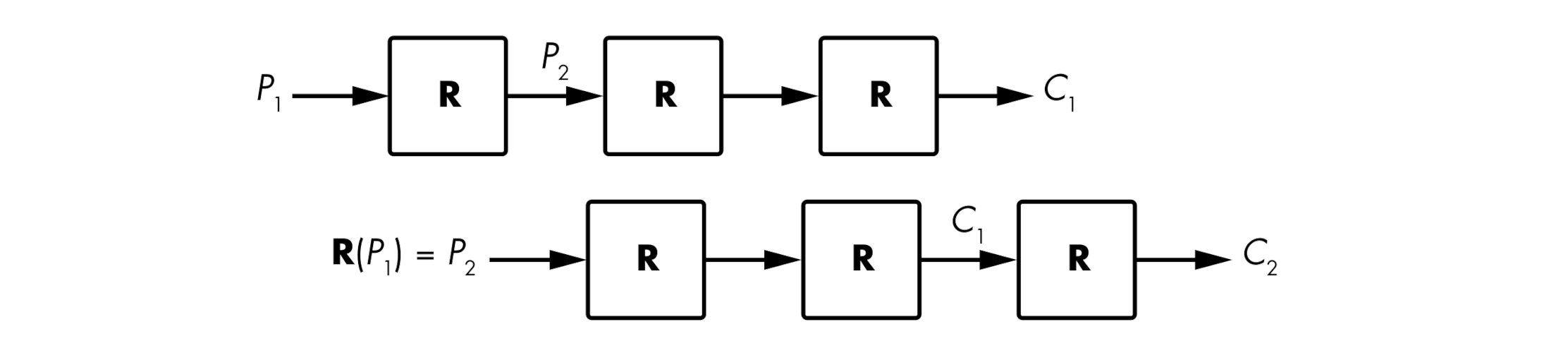

Computing a block cipher means computing a sequence of rounds. In a block cipher, a round is a basic transformation that is simple to specify and to implement, and which is iterated several times to form the block cipher’s algorithm.

The round functions are usually identical algorithms, but they are parameterized by a value called the round key. Two round functions with two distinct round keys will behave differently, and therefore will produce distinct outputs if fed with the same input. Round keys are keys derived from the main key, \(K\), using an algorithm called a key schedule.

Slide attacks look for two plaintext/ciphertext pairs \((P_1, C_1)\) and \((P_2, C_2)\), where \(P_2 = R(P_1)\) if \(R\) is the cipher’s round.

One potential byproduct and benefit of using round keys is protection against side-channel attacks, or attacks that exploit information leaked from the implementation of a cipher. If the transformation from the main key, \(K\), to a round key, \(K_i\), is not invertible, then if an attacker finds \(K_i\), they can’t use that key to find \(K\). Unfortunately, few block ciphers have a one-way key schedule. The key schedule of AES allows attackers to compute \(K\) from any round key, \(K_i\).

Substitution–Permutation networks

In the design of a block cipher, confusion and diffusion take the form of substitution and permutation operations, which are combined within substitution–permutation networks (SPNs). Substitution often appears in the form of S-boxes, or substitution boxes, which are small lookup tables that transform chunks of 4 or 8 bits.

S-boxes must be carefully chosen to be cryptographically strong: they should be as nonlinear as possible (inputs and outputs should be related with complex equations) and have no statistical bias (meaning, for example, that flipping an input bit should potentially affect any of the output bits).

The permutation in a substitution–permutation network can be as simple as changing the order of the bits, which is easy to implement but does not mix up the bits very much. Instead of a reordering of the bits, some ciphers use basic linear algebra and matrix multiplications to mix up the bits.

Security

There are two must-know attacks on block ciphers: meet-in-the-middle attacks, a technique discovered in the 1970s but still used in many cryptanalytic attacks (not to be confused with man-in-the-middle attacks), and padding oracle attacks, a class of attacks discovered in 2002 by academic cryptographers, then mostly ignored, and finally rediscovered a decade later along with several vulnerable applications.