Down streams

Stream ciphers are deterministic. This allows for decrypting by regenerating the pseudorandom bits used to encrypt. Stream ciphers take two values: a key and a nonce. The key should be secret and is usually 128 or 256 bits. The nonce does not have to be secret, but should be unique for each key and is usually between 64 and 128 bits. The nonce is sometimes called the IV, for initial value.

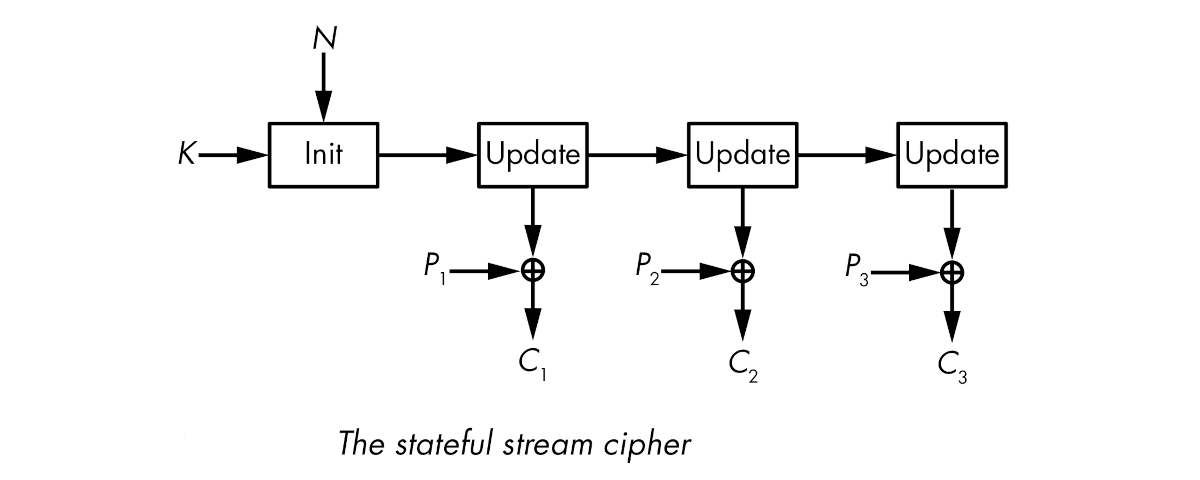

Stateful stream ciphers have a secret internal state that evolves throughout keystream generation. The cipher initialises the state from the key and the nonce and then calls an update function to update the state value and produce one or more keystream bits from the state.

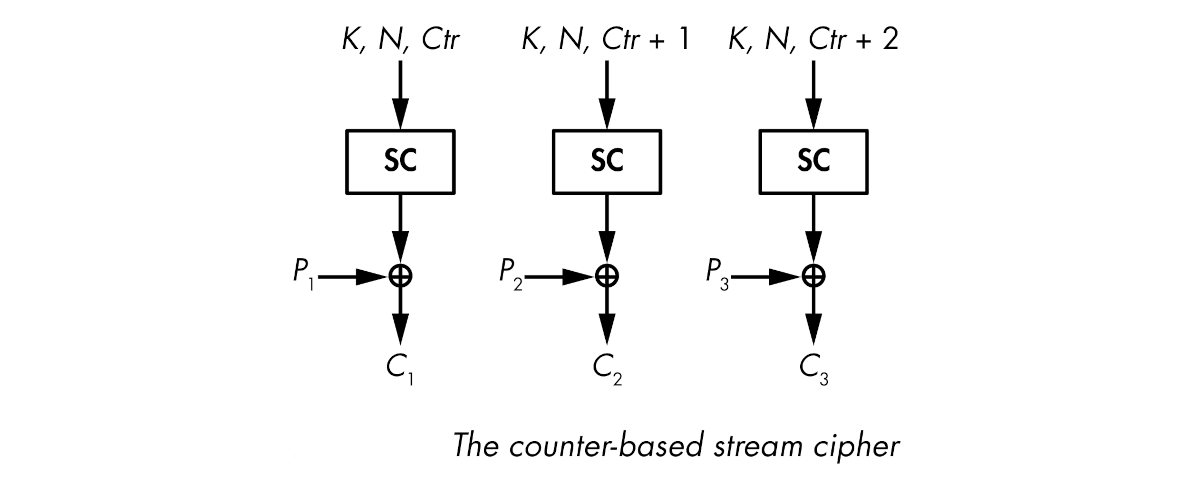

Counter-based stream ciphers produce chunks of keystream from a key, a nonce, and a counter value. No secret state is memorised during keystream generation.

Linear Feedback Shift Registers

Linear feedback shift registers (LFSRs) are FSRs with a linear feedback function, a function that is the XOR of some bits of the state. Thanks to this linearity, LFSRs can be analyzed using notions like linear complexity, finite fields, and primitive polynomials.

The choice which bits are XORed together is essential for the period of the LFSR and thus for its cryptographic value. The position of the bits must be selected such to guarantee a maximal period (\(2^n – 1\)). The maximal period of an n-bit LFSR is \(2^n – 1\), not \(2^n\), because the all-zero state always loops on itself infinitely.

Take the indices of the bits, from 1 for the rightmost to n for the leftmost, and write the polynomial expression \(1 + X + X^2 + . . . + X^n\), where the term \(X^i\) is only included if the \(i\)th bit is one of the bits XORed in the feedback function. The period is maximal if and only if that polynomial is primitive.

To be primitive, the polynomial must be irreducible, meaning that it ca not be factorised (written as a product of smaller polynomials).

Using an LFSR as a stream cipher is insecure. If \(n\) is the LFSR’s bit length, an attacker needs only \(n\) output bits to recover the LFSR’s initial state, allowing them to determine all previous bits and predict all future bits. This attack is possible because the Berlekamp–Massey algorithm can be used to solve the equations defined by the LFSR’s mathematical structure to find not only the LFSR’s initial state but also its feedback polynomial. It isn’t even needed to know the exact length of the LFSR; repeat the Berlekamp–Massey algorithm for all possible values of \(n\) until you hit the right one.

RootMe challenges

Security

Many things can go wrong with stream ciphers, from brittle, insecure designs to strong algorithms incorrectly implemented.

The most common failure seen with stream ciphers occurs when a nonce is reused more than once with the same key. This produces identical keystreams, allowing an adversary to break the encryption by XORing two ciphertexts together.