Classical ciphers

Classical ciphers are doomed to be insecure because they’re limited to operations you can do in our heads or on a piece of paper. They lack the computational power of a computer and are easily broken by simple computer programs.

Caesar cipher

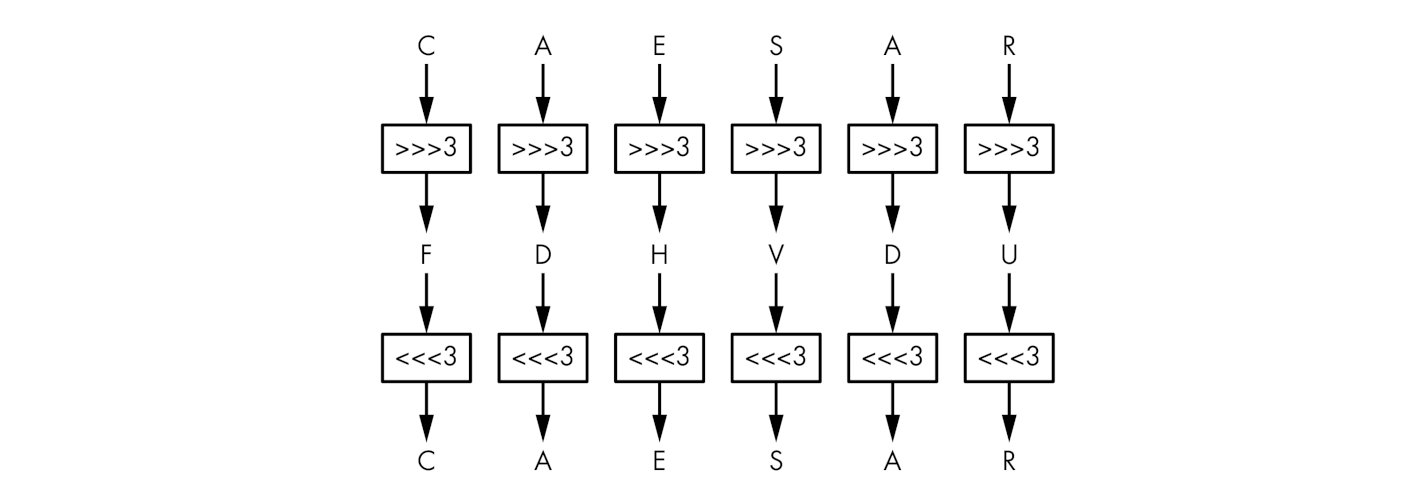

One of the most widely known historical encryption methods is the Caesar cipher. According to the Roman historian Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (c. 70–130 CE), Julius Caesar used this cipher to encrypt military messages, shifting all letters of the plaintext three places to the right.

Although the Caesar cipher is not useful for modern cryptographic needs, it does contain all the fundamental concepts needed for a cryptography algorithm

A plaintext message

An algorithm: shift every letter

A key: for example +3

A ciphertext

This is, essentially, the same structure used by all modern symmetric algorithms. Because there are only 26 letters in the English alphabet, the key space is 26 (in English).

The mathematical representation of Caesar’s method of shifting three to the right is:

The Caesar cipher is super easy to break: to decrypt a given ciphertext, simply shift the letters three positions back to retrieve the plaintext. The Caesar cipher may have been strong enough during the time of Crassus and Cicero because no secret key was involved (it is always 3), and it was assumed attackers were illiterate or too uneducated to figure it out. This assumption no longer holds true.

The Caesar cipher can be made more secure by using a variable secret shift value instead of always using 3, but that does not help much because an attacker could easily try all 25 possible shift values until the decrypted message makes sense.

The Vigenère cipher

About 1500 years later, in 1553, a meaningful improvement of the Caesar cipher appeared in the form of the Vigenère cipher, created in the 16th century by Giovan Battista Bellaso. The name Vigenère comes from Blaise de Vigenère, who invented a different cipher in the 16th century, but due to historical misattribution, Vigenère’s name stuck.

The Vigenère cipher is a method of encrypting alphabetic text by using a series of different mono-alphabet ciphers selected based on the letters of a keyword. Bellaso also added the concept of using any keyword, thereby making the choice of substitution alphabets difficult to calculate.

The Vigenère cipher became favoured and was used during the American Civil War by Confederate forces and during WWI by the Swiss Army, among others. For many years, Vigenère was considered very strong, even unbreakable. In the nineteenth century, Friedrich Kasiski published a technique for breaking the Vigenère cipher.

The math for Vigenère looks very similar to that of Caesar, with one important difference: the value \(K\) changes:

The \(i\) denotes the current key with the current letter of plaintext and the current letter of ciphertext. Many sources use \(M\) (for message) rather than \(P\) (for plaintext) in this notation.

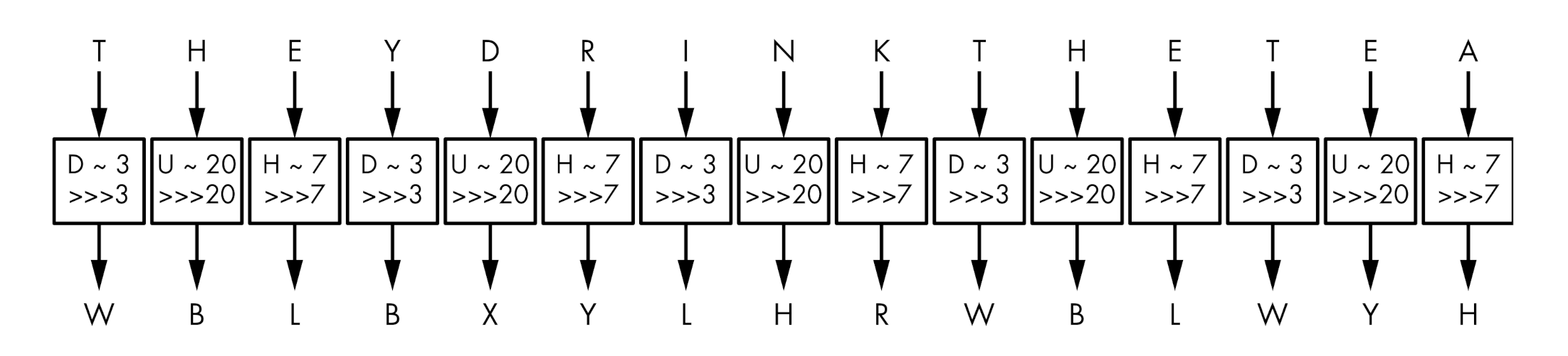

IOW, it is similar to the Caesar cipher, except that letters aren’t shifted by three places but rather by values defined by a key, a collection of letters that represent numbers based on their position in the alphabet. For example, if the key is DUH, letters in the plaintext are shifted using the values 3, 20, 7 because D is three letters after A, U is 20 letters after A, and H is seven letters after A. The 3, 20, 7 pattern repeats until the entire plaintext is encrypted.

The Vigenère cipher is clearly more secure than the Caesar cipher, yet it’s still fairly easy to break:

The first step to breaking it is to figure out the key’s length. If in the ciphertext a group of letters appears often, this gives clues about the key length. If for example a group of three letters (WBL) appears twice in a ciphertext at nine-letter intervals, this suggests that the same three-letter word was encrypted using the same shift values, producing WBL each time. A cryptanalyst can then deduce that the key’s length is either nine or a value divisible by nine (that is, three).

The second step to breaking the Vigenère cipher is to determine the actual key using a method called frequency analysis, which exploits the uneven distribution of letters in languages. For example, in English, E is the most common letter, so if you find that X is the most common letter in a ciphertext, then the most likely plaintext value at this position is E.

Breaking ciphers

Trying to figure out the workings of a cipher, first identify its two main components: its permutation and a mode of operation.

A permutation is a function that transforms an item (a letter or a group of bits) such that each item has a unique inverse. Most classical ciphers work by replacing each letter with another letter. In the Caesar and Vigenère ciphers, the substitution is a shift in the alphabet. The alphabet or set of symbols can vary: it could be the Arabic alphabet; instead of letters, it could be words, numbers, or ideograms, etc.

To be secure, a cipher’s permutation should satisfy three criteria:

The permutation should be determined by the key, to keep the permutation secret as long as the key is secret. In the Vigenère cipher, if you don’t know the key, you don’t know which of the 26 permutations was used; that makes it harder to decrypt.

Different keys should result in different permutations. If not, it becomes easier to decrypt without the key: if different keys result in the same permutations, there are fewer distinct keys than distinct permutations, and therefore fewer possibilities to try when decrypting without the key.

The permutation should look random: patterns make a permutation predictable for an attacker, and therefore less secure.

A mode of operation is an algorithm that uses a permutation to process messages of arbitrary size. It mitigates the exposure of duplicate letters in the plaintext by using different permutations for duplicate letters.

The mode of the Caesar cipher repeats the same permutation for each letter, and in the Vigenère cipher letters at different positions undergo different permutations: if the key is N letters long, then N different permutations will be used for every N consecutive letters. This can still result in patterns in the ciphertext because every Nth letter of the message uses the same permutation. That’s why frequency analysis works to break the Vigenère cipher.

Frequency analysis can be defeated if the Vigenère cipher only encrypts plaintexts that are of the same length as the key. In which case, another problem appears: reusing the same key several times exposes similarities between plaintexts. For example, with the key KYN, the words TIE and PIE encrypt to DGR and ZGR, respectively. Both end with the same two letters (GR), revealing that both plaintexts share their last two letters as well. Finding these patterns shouldn’t be possible with a secure cipher.

To build a secure cipher, combine a secure permutation with a secure mode. Ideally, this combination prevents attackers from learning anything about a message other than its length.

One-Time Pad

A classical cipher can not be secure unless it comes with a huge key, and encrypting with a huge key is impractical. The one-time pad is such a cipher, and it is the most secure cipher.

The one-time pad takes a plaintext, \(P\), and a random key, \(K\), that is the same length as \(P\) and produces a ciphertext \(C\), defined as

where \(C\), \(P\), and \(K\) are bit strings of the same length and where ⊕ is the bitwise exclusive OR operation (XOR), defined as \(0 ⊕ 0 = 0\), \(0 ⊕ 1 = 1\), \(1 ⊕ 0 = 1\), and \(1 ⊕ 1 = 0\).

The concept behind a one-time pad is that the plaintext is somehow altered by a random string of data so that the resulting ciphertext is truly random. To truly be a one-time pad, by modern standards, a cipher needs two properties:

The key is only used once. After a message is enciphered with a particular key, that key is never used again. This makes the one-time pad quite secure, but also very impractical for ongoing communications.

The key must be at least as long as the message. That prevents any patterns from emerging in the ciphertext.

The one-time pad guarantees perfect secrecy: even if an attacker has unlimited computing power, it’s impossible to learn anything about the plaintext except for its length. The one-time pad’s decryption is identical to encryption; it is just an XOR:

We can verify \(C ⊕ K = P ⊕ K ⊕ K = P\), because XORing \(K\) with itself gives the all-zero string 000 . . . 000.

While one-time pads provide perfect secrecy if generated and used properly, small mistakes can lead to successful cryptanalysis.

A one-time pad can only be used one time: each key \(K\) should be used only once. If the same \(K\) is used to encrypt \(P_1\) and \(P_2\) to \(C_1\) and \(C_2\), then an eavesdropper can compute the following:

An eavesdropper could thus learn the XOR difference of \(P_1\) and \(P_2\), information that should be kept secret.

One-time pads were used by the British Special Operations Executive during WWII, by KGB spies, by the NSA, and are still used for communications today, but only for the most sensitive communications. The keys must be stored in a secure location, such as a safe, and used only once for very critical messages. The keys for modern one-time pads are simply strings of random numbers sufficiently large enough to account for whatever message might be sent.

Vernam cipher

The Vernam cipher is a type of one-time pad. Gilbert Vernam proposed a stream cipher that would be used with teleprinters. It would combine character by character a prepared key that was stored on a paper tape, with the characters of the plaintext to produce the ciphertext. The recipient would again apply the key to get back the plaintext.

Vernam’s method uses the binary XOR (Exclusive OR) operation applied to the bits of the message.

RootMe challenges

Security

A cipher is secure if, even given a large number of plaintext–ciphertext pairs, nothing can be learned about the cipher’s behaviour when applied to other plaintexts or ciphertexts.